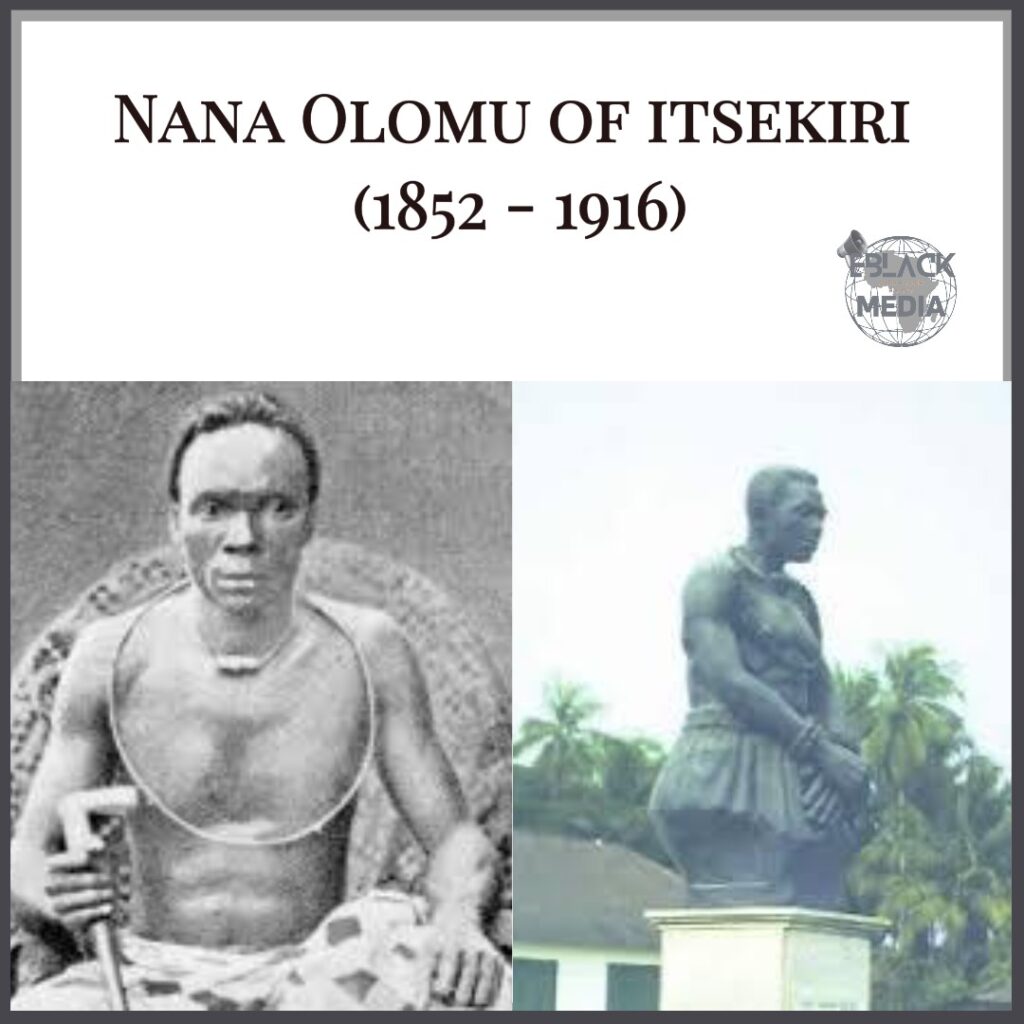

Nana Olomu, a prominent figure in the history of Nigeria’s Niger Delta region, stands out not just as a chief, but as a symbol of the complexities surrounding colonial diplomacy and indigenous leadership. His life, spanning from 1852 to 1916, is a tale of power, trade, and resistance—a narrative that continues to resonate in contemporary discussions about colonialism and indigenous rights.

Early Life and Ascendancy

Born in 1852, Nana Olomu rose to prominence in the Itsekiri community, known for its rich cultural heritage and strategic trading position along the Benin River. In 1851, British governance began to infiltrate local power structures with the appointment of the first Governor of Benin River, an Itsekiri chief named Idiare. This new colonial framework intended to establish a rotation of power between two noble families, the Emaye and the Ologbotsere. However, upon the death of his father, an Ologbotsere, Nana Olomu ascended to the governorship directly, a decision that would define his political landscape.

A Broker of Trade and Diplomacy

As the fourth Governor, Nana Olomu was not just a political leader; he was also a thriving palm oil merchant, understanding the economic intricacies of trade. In 1884, he signed a treaty granting the British further rights to trade in Itsekiriland, marking a significant period of collaboration between the Itsekiri people and colonial powers. This relationship was initially characterized by a mutual benefit, with Nana Olomu serving as a vital intermediary in trade between the British and local populations.

However, the colonial context began to change dramatically—the 1884-1885 Berlin Conference that partitioned Africa among European powers led to heightened tensions. The British, motivated by their ambitions to streamline trade routes, began to bypass the Itsekiri middlemen in favor of direct dealings with the Urhobo people, further destabilizing the region’s traditional economic structures.

The Decline of Relations

As the British pursued new strategies of trade, direct treaties established with the Urhobo people infuriated Olomu and his community. In retaliation, he orchestrated attacks on Urhobo villages that had engaged in trade with the British, leading to a vicious cycle of conflict that ultimately spelled disaster for the Itsekiri. The colonial response was swift; British forces cracked down on the Olomu-led resistance, and by 1894, many Itsekiri chiefs, under pressure, signed a new treaty directly with the British.

Nana Olomu’s leadership faced its most significant crisis in 1894 when he was arrested and deported to the Gold Coast, symbolizing the profound shift in power dynamics. The once-collaborative relationship had devolved into one marked by resistance, betrayal, and ultimately, oppression.

A Call for Justice and Recognition

Nana Olomu’s exile was not forgotten. In 1899, the Aborigines’ Protection Society in the UK raised concerns about the arbitrary treatment he endured and the lack of a thorough investigation into his case. His appeals for better conditions and acknowledgment of his contributions resonated within British political circles, highlighting the contradictions of colonial governance, where indigenous rights were frequently overlooked in favor of imperial interests.

The British government’s refusal to allow his return to his homeland underscored a broader systemic neglect of indigenous leaders and their rights.

Legacy and Remembrance

Today, Nana Olomu’s memory is preserved in the form of the Nana Living History Museum located in Koko, Delta State. This museum not only honors Olomu’s legacy but also serves as a testament to the cultural and historical richness of the Itsekiri people. It provides a space for reflection on the impacts of colonialism and the invaluable contributions of local leaders in shaping Nigeria’s history.

Conclusion

Nana Olomu’s life epitomizes the struggles of indigenous governance amidst the waves of colonial encroachment. As we delve into his story, we uncover the intricate tapestry of trade, diplomacy, and resistance that defined a critical era in Nigerian history. His legacy reminds us of the importance of recognizing and preserving Indigenous narratives in the face of colonial histories—a vital pursuit in forging a more equitable understanding of our collective past.