ETHNONYMS: Aussa, Haoussa, al Hausin; Ama or Azna, Bunjawa, Maguzawa (non-Muslims); Afnu (the Kanuri name) or Afunu

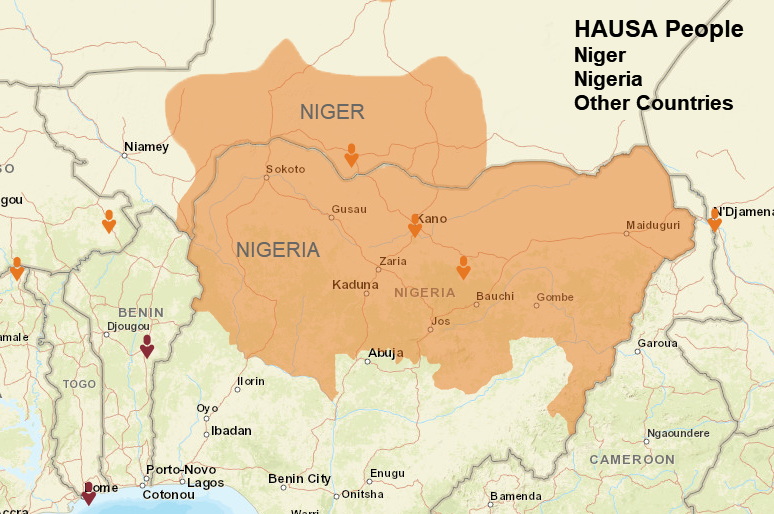

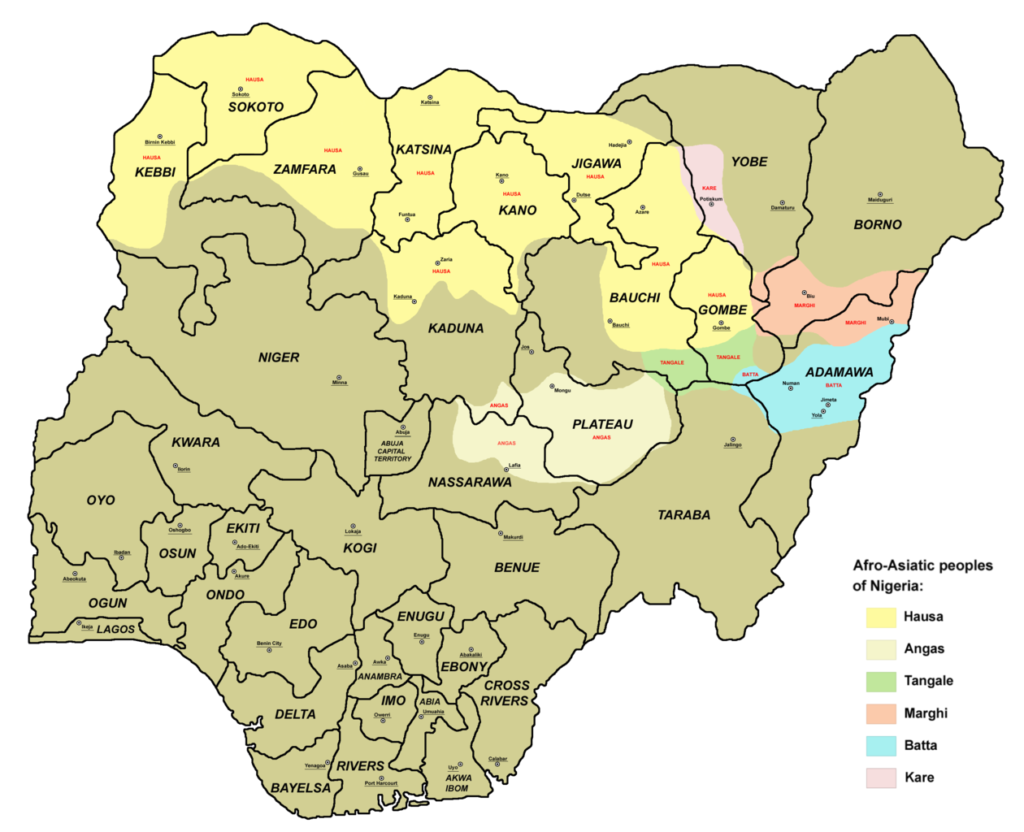

The Hausa people constitute the largest ethnic group in Africa and one of the largest in West Africa. Most of them live in the Sahelian regions of northern Nigeria and southeast Niger, although a sizable population also inhabits parts of Sudan, Cameroon, Ghana, Côte d’Ivoire, and Chad. Communities made up primarily of Hausa people can be found all over West Africa and along the traditional Hajj route through the Sahara Desert, particularly in and around the town of Agadez.

A small number of Hausa have also migrated to North Africa, specifically to Libya, and to major coastal towns in the region, including Lagos, Accra, Kumasi, and Cotonou. In West Africa, however, the majority of Hausa live in tiny towns or villages where they cultivate crops and rear cattle and other animals. They communicate in Hausa, an Afro-Asian language belonging to the Chadic people.

The Hausa originated in northern Nigeria and south-central Niger. They are a racially heterogeneous but culturally homogeneous people.

Wealthy merchants hold the highest social ranks alongside the politically influential and the intelligentsia. The Hausa people have a long history of engaging in extensive nomadic trading.

With a population of over 30 million, the Hausa are primarily Muslim, ranked as the fourth biggest Muslim group in the world, with about 36,000 acknowledged Christians and a significant proportion also adhering to African traditional religions.

Language

Hausa is a Chadic language, linked to Hebrew, Arabic, Berber, and other languages of the Afroasiatic Family. Stress and tone must be used appropriately. Although Hausa has a centuries-old literary legacy and was originally written in Arabic script, it is also the language of trade and, after Swahili, the most frequently spoken language in Africa.

Settlements

The Hausa divide their communities into hamlets, towns, and cities. Foreigners, including Tuareg, Arabs, Nupe, Kanuri, and others, have their own wards in the towns. The inhabitants of the walled capital cities reside in walled complexes with internal courtyards. Rich people’s homes are plastered with arabesques and whitewashed. There are separate quarters for ladies. Between sixty and one hundred people can live in urban complexes. Despite having the highest status among urbanites, the Hausa people are predominantly rural. Every village has multiple hamlets in addition to a capital, which is separated into wards that house families in the same occupational category. Conventional village complexes are walled or fenced and made of cornstalks, mud, or baked clay.

A typical compound would have an entrance hut, a communal kitchen and work space that is available to all, a hut designated for the compound head, and individual huts for each of his wives. Concrete, rectangular dwellings are more recent. A rural compound can have anywhere from one to thirty residents, with an average of ten.

Economy

Both commercial activity and subsistence. The primary economic activity is agriculture. The main food is grain, which includes rice, millet, maize, and Guinea corn. The Hausa cultivate and consume a wide range of vegetables as well as root crops. Most of the produce is exported, but some cotton and peanuts are processed and utilized locally. The hoe is the primary tool used by the Hausa people in their double- and intercropping practices. The Hausa eat meat, yogurt, and butter from the Fulani cattle.

The majority of men work in a second, ascriptive, and ranking profession. Examples of them are butchering, craftsman, commerce, Islamic cleric (imam), aristocratic officeholder, scholar, and musician. As devout Muslims, urban women—rural women less so—live in seclusion and are thus financially dependent on their husbands; from behind the walls of the compound, however, they engage in commercial activity, mostly to pay for their daughters’ dowries. Their domestic demeanor is the source of their work, which includes sewing and selling prepared foods and jewelry.

Arts of Industry. Only in areas where there is a guaranteed demand for handcrafted goods are there full-time specialists. Tannin, leatherworking, saddlery, weaving, dying, woodworking, and smithing are examples of crafts performed by men. Since the beginning of Hausa traditions, iron has been mined, smelted, and used in various ways. A lot of blacksmiths are inherited, and they are organized like guilds.

Exchange. Trade is diverse and intricate. Traders who operate in a specific market are distinct from those who transact in multiple marketplaces across large distances. Even in the nineteenth century, the Hausa were able to meet all of their needs thanks to this dual trade approach and the contributions of the Cattle Fulani. The marketplaces hold social and economic importance in Hausa society. Well-dressed young ladies who are ready for marriage congregate there, as do male acquaintances and relatives. The Hausa use the size and frequency of the marketplaces to distinguish between rural and urban towns.

Other than market exchange, there is also customary exchange. Exchanges of gifts take place during life-cycle events like births, namings, marriages, and deaths; other exchanges are governed by politics and religion (tithes, fixed holidays, alms, and patronage/clientage interactions).

Separation of Work. The Hausa community has long upheld various divisions of labor. Men are generally selected to roles in public administration, while some women do have appointed positions in the palace. Work roles are determined by gender, and one’s class influences the type of work one might do. Women who work in jobs that generate revenue might keep the money they make. Many mothers who trade rely on their children to run for them because of purdah.

Tenure of Land. With the assistance of his sons, the rural householder farms; he gives his sons modest plots from the old farm, which he expands as they get older. The bush is cleared to make way for new family fields.

Kinship

Groups of Kin and Decline. Even though the Hausa society is patriarchal and the home group is built on agnatic ties, descent is essentially bilateral; only the urban intellectuals and political aristocracy adhere to pure patrilineality, while everyone else practices bilaterality.

Terminology related to Kinship. There are too many different ways to classify Hausa kinship terms under established anthropological categories. Cross cousins, on the other hand, are also referred to and addressed as abokan wasa (joking relations), and special terms distinguishing elder and younger brother and sister may also be applied to both parallel and cross cousins. For instance, a man’s siblings and his parallel or cross cousins are called ‘yanuwa (children of my mother).

Marriage and family

union. In adult Hausa society, marriage is practically universal. A man may have up to four wives at any given moment in an ideal polygynous virilocal/patrilocal marriage. The Hausa word for “co-wife” is kishiya, which comes from the word for “jealousy.” Co-wife relations are frequently, but not always, described by this term. Men are rarely single after becoming married, even after divorce, as most are polygynous; women, on the other hand, are nearly half divorced at some point, but they rarely stay single for very long because of the pressure to get married and start a family. Women are identified by significant societal disparities based on their marital status. Girls typically marry between the ages of 12 and 14. The literature contains some disagreements about the courteous

The bride-price, which is presented to her by the groom’s family, and the dowry that the bride’s family provides for her are symbols of marriage. The degree of wife seclusion and whether the marriage is a kin or nonkin union are the two factors that determine how marriage is defined. Marriage between two cross-cousins is recommended.

Domestic Unit. The ideal household is the agnatically based gandu (family farm), formed by a man with his sons and their wives and children. After the senior male’s death, the brothers may stay on together for a time. More frequently, each brother’s household becomes a separate economic unit.

Inheritance. Consistent with Islamic practice, a woman can own and inherit in her own right, but her inheritance rights are subordinate to those of men. All of the wives married to a man at the time of his death are entitled, together with their children, to share one-quarter of his total estate if there are no agnatic descendants, or one-eighth of his estate if there are agnatic descendants.

Even after marriage, women hold property like homes and land alongside consanguines, and they only get half as much as their brothers.

Collateral is the right to succeed the agnatic group’s leader and the compound’s leader. Land is passed down through the male line; brothers own the gandu collectively.

Socialization. After giving birth, women follow a one and a half to two year period during which they are not allowed to have sexual relations with the child. After being weaned onto soft foods, toddlers are introduced to a regular diet. When the mother is busy, an older sister tends to the infant on her back; this leads to a unique bond between an adult male and his elder sister.

Boys and girls receive distinct treatment starting in infancy. Boys are favored because, as they grow older, they come to understand that they are better than girls, which causes them to separate from them and associate with things that are associated with men. It is essential that males grow away from their mothers. Girls are conditioned to identify with their sex roles; as they get older, they are taught domestic (female) skills. They are warned to treat men with deference and submission. Boys and girls are rigorously sex-stereotyped into acceptable conduct while they are young.

Sociopolitical Organization

Social Organization. One of the most salient principles in Hausa society is the segregation of adults according to gender. Throughout Hausaland, seclusion of married women is normative, and the extradomestic impact of sexual segregation and stratification is that women are legal, political, and religious minors and the economic wards of men. Although women are central to kinship matters, they are excluded from extradomestic discussion and decision making. Both within the household and in the public domain, patriarchal authority is dominant and reinforced by spatial separation of the sexes.

The uwar gida is the senior spouse of the mai gida, the head of the complex. She might mediate little conflicts between the inhabitants and assist and counsel the younger female residents. The masculine head of the household or compound has domestic control.

Males and females form close friendships with others of the same sex from an early age; these friendships are characterized by reciprocal interactions and persist into adulthood. Women solidify their binding bonds more than males do, probably because of their solitude. Just as men create formal partnerships that highlight status inequalities (patron/client), so do women.

Political Structure. The emirates, or centralized kingdoms, are the main organizational units; districts are secondary, while village areas are tertiary. The organizational structure is hierarchical.

From the sixteenth century to the middle of the twentieth century, the foundation of Hausa administration was provided by the emirates’ systems of family, clientship, office, and, in the past, slavery. The relationship between commoners and kings is governed by rank.

“The system of titled offices, which is the basis for both traditional and modern government, is composed of distinct legal corporations with distinct rights, powers, and responsibilities, as well as special relationships to the throne and other offices, as well as special lands, farms, compounds, horses, praise songs, clients, and, historically, slaves” (Smith 1965, 132). Major offices have historically been divided across descent groups in the majority of states, blending rank and ancestry. The old offices were territorially oriented, with associated responsibilities and tasks, and varied in terms of power, function, and rewards. The several professional groups in a community assign titles, mirroring the levels of the central governmental hierarchy.

Men of uneven wealth, rank, and position are linked through clientship. In this mutually beneficial arrangement, the client receives the maximum amount of protection, food, and housing and the smallest amount of advise regarding his affairs. The client may be called upon by the patron to act as his retainer.

When Usman dan Fodio, the Fulani political and religious leader, launched his successful jihad against the king of Gobir in 1804, he applied his concept of government to Kano. He did so by adhering to the fundamental idea of a theocracy within a legalistic framework, wherein government and its chief agent, the emir, were seen as instruments of Allah.

Social Regulating. Islamic law serves as the emir’s guide when it comes to legal matters. Legal questions are answered by the Quran, which is the word of Allah, coupled with its hadith, the customs of the Prophet Mohammed, and the rules of secular logic. Fundamentally, the Islamic canon law, or Sharia, is an ethical code of conduct. Adherence to Hausa and Islamic custom is enforced through the threat of shame and exclusion.

Tension. The Hausa have three options for resolving conflicts: they can go to court, accept mediation, or leave it to Allah. The fundamental procedure entails respect for elder mediation.

Religion and Expressive Culture

Beliefs in religion. Muslims make up almost 90% of the Hausa people. “Many of the fundamental principles of Hausa society are Islamic since the traditional way of life and Islamic social norms have been blended for such a long period” (Adamu 1978, 9). Islam has been spread throughout West Africa by Hausa traders. It consists of ethical rules and obligations. Adherence to Hausa and Islamic custom is enforced through the threat of shame and exclusion.

Tension. The Hausa have three options for resolving conflicts: they can go to court, accept mediation, or leave it to Allah. The fundamental procedure entails respect for elder mediation.

The five pillars of Islam—profession of faith, five daily prayers, almsgiving, fasting during Ramadan, and at least one pilgrimage to Mecca (the hajj)—must be observed by adherents. There are adherent sects (brotherhoods) in Hausa society; the Tijaniya, Qadriya, and Ahmadiyya have been significant. The Hausa variety of Islam places a strong emphasis on wife isolation, despite the belief that the practice is more of a status symbol than a proof of religious sincerity.

Spirit cults continue, even among certain Muslims, as they did among the Maguzawa pagans. There are more female adepts than male among the Bori; followers of this religion think that certain spirits from the Bori pantheon inhabit their followers.

Practitioners of Religion. Even though they do not have any church duties or spiritual power, imams and teachers (mallamai; sing. mallam) do occasionally take on or accept some degree of spiritual authority.

Ceremonies. Men are expected to go to the mosque on Fridays for prayers. The three major annual holidays of Ramadan, Id il Fitr, and Sallah are observed by both men and women. Life-cycle events are also marked, including marriage, death, puberty, and birth.

Arts. The Hausa employ Islamic design in their architecture, ceramics, textiles, leather goods, and weaving. The arts are restricted to those forms sanctioned by Islam. Music serves a variety of purposes and audiences in Hausa culture, including royalty, professional guilds, and dancing enthusiasts. Every category has its own set of instruments, which range from wind and string to percussion. Poetry is part of the written tradition of the learned as well as the oral tradition of the praise singers and oral historians.

health care. There is a tricultural system made up of Western medicine supplemented by solid traditional foundations within the framework of a mostly Islamic approach. The Bori spirit-possession cult is used for a variety of healing techniques, one of which is identifying the specific spirit causing the patient’s illness.

Death and Eternity. The Islamic way of burial is followed. According to Islamic belief, after death, the person enters either heaven (paradise) or hell.

Hausa Culture

Outfits

Throughout the Middle Ages, the Hausa were well-known for their leatherworking, cotton goods, leather sandals, metal locks, horse equipment, and cloth weaving and dying. They also exported these goods to North Africa and other parts of West Africa (Hausa leather was mistakenly known to medieval Europe as Moroccan leather). They were known as “bluemen” since they were frequently identified by their indigo blue attire and insignia. Traditionally, they traveled on elegant horses and Saharan camels. The Hausa people of West Africa have been using tie-dye for millennia, and Kano, Nigeria, is home to famous indigo dye mines. After the clothing has been tie-dyed, elaborate embroidery in traditional designs is added.

There have been suggestions that the tie-dyed clothing associated with hippie fashion was inspired by these African traditions.

The Hausa people wear flowing, flowy dresses and pants as part of their traditional attire. There are large ventilation vents on both sides of the gowns. The pants are rather snug around the legs, but they are loose in the top and middle. Turbans and leather sandals are also common. The extravagant attire of the men, a wide flowing gown known as Babban riga (also called by numerous other names due to modification by many ethnic groups nearby the Hausa; see indigo Babban Riga/Gandora), makes them easily identifiable. Exquisite embroidery motifs are typically seen around the neck and chest area of these big, flowing robes.

Durbar Festival

Annual religious and horseback celebrations known as the Durbar festival take place in a number of Nigerian cities, including Kano, Katsina, Sokoto, Zazzau, Bauchi, and Bida. The celebrations of Eid al-Adha and Eid al-Fitri, which are observed by Muslims, fall on the same day as the completion of Ramadan.

Prayers open the ceremony, which is followed by a colorful horse-drawn procession led by the Emir and his entourage and concluded at the Emir’s palace with musical accompaniment. Nearly every city in northern Nigeria hosts durbar festivals, which have been a tradition for more than 200 years.

Architecture

The Hausa architecture of the Middle Ages is arguably among the most exquisite yet little-known. Many of their early palaces and mosques are vividly colored, with complex emblems or fine engravings carved onto the exterior. The Hausa word for architecture is Tubali, which is the name given to this architectural style. The historic city walls of Kano were constructed to offer protection to the expanding populace.

Between 1095 and 1134, Sarki Gijimasu lay the groundwork for the wall’s construction, which was finished in the middle of the fourteenth century. The walls were extended to their current location in the sixteenth century. The gates, which date back to when the walls were built, were meant to regulate who might enter and leave the city.

Hausa buildings are distinguished by the use of classic white stucco and plaster for home fronts, multi-story buildings for the social elite, parapets connected to their military/fortress building past, and cubic structures built with dry mud bricks. The façade may occasionally be painted in vibrant colors to reveal information about the inhabitant, or they may be embellished with a variety of abstract relief motifs.

Union

Islamic ritual and indigenous rituals are combined in Northern Nigerian engagement and marriage ceremonies. For Muslims, engaging in sexual relations and procreating requires marriage, or Fatiha. Depending on the hosts’ resources, it is also greatly praised. Typically, the marriage ceremony lasts for one week, concluding on a Sunday.

But as soon as the bride’s parents receive the marriage proposal, plans get underway. The groom buys a variety of household and cosmetic items known as Kayan Zance, such as perfumes, shoes, shirts, and beauty cream, and brings them to the bride’s home as soon as the bride’s parents approve the marriage proposal.

A date for the engagement is then decided upon after a group of men known as Kudin Gaisuwa are sent to the bride’s home with money. The reception following the engagement ceremony is hosted at the bride’s representative’s home, and the prospective husband is requested to bring some candy and kola nuts for the occasion. Usually, the event happens in the evening.

Some customs are observed prior to the marriage ceremony. These include the Thursday-night Kamun Ango and Friday-night Zaman Ajo.

Ceremony of Naming

According to Hausa tradition, a wife’s daily bath ritual begins as soon as she becomes pregnant and delivers birth, when she boils water and gathers firewood for cooking. A sheep or ram is killed one week after delivery, and kola nuts and other food items are prepared. A dish called kauri is made and given to family and friends on the third day following delivery, signifying the birth of the child. Well-wishers receive notification on the sixth day following birth asking them to visit the host’s home the next day for the naming ceremony.

The women remain inside the house and the males remain outside on the day of the naming ceremony. The Imam, who is typically the first to get invitations, frequently arrives last. The child’s father gives him the child’s name when he arrives, and the Imam does prayers and declares the child’s name in public.

Religious Festivals

Hausaland celebrates the following three important Islamic holidays: Eid-El-Fitr, Eid-El-Kabir, and Eid-El-maulud.

In the Islamic calendar, the first day of Shawwal, the month that comes after Ramadan, coincides with Eid al-Fitr. It is a time to celebrate the end of a month full of blessings and joy with family and friends, as well as to contribute to those in need.

During the final few days of Ramadan, leading up to Eid, every Muslim family donates a specific sum to the less fortunate. This contribution is in the form of real food, such as rice, barley, dates, rice, etc., to make sure that those in need can celebrate and have a festive meal. The term “sadaqah al-fitr” refers to this donation (charity of fast-breaking).

Muslims congregate outside of mosques or other public spaces early on the day of Eid to pray. This is a sermon followed by a brief prayer for the congregation.

Following the Eid prayer, Muslims typically disperse to visit various relatives and friends, exchange gifts, particularly with youngsters, and express well-wishes for the occasion over the phone to distant relatives. Traditionally, these events last for three days. The full three days are recognized as official government and school holidays in the majority of Muslim nations.

Eid-el Adha, also known as Eid-el Kabir, is a time for introspection and sobriety over how well humanity has complied with Allah’s numerous commands. Now is the moment to consider if the Hausa people have appropriately returned Allah’s kindness and patience with the faith and gratitude that all Muslims, and all creatures in general, are obligated to show at all times.

As God revealed to Prophet Ibrahim (May Allah’s peace be upon him) through dreams, it serves as a reminder of the unimaginable things that could have happened to humanity if it were not for Allah’s kindness in providing Ishmael with a ram just as his father was about to kill him as a sacrifice. Without a doubt, supernatural intervention averted what would have been humanity’s sad outcome. Furthermore, because of this,

in addition to the fact that Hausas observe moderation during celebrations, and that Eid-el-Kabir shares a tight relationship with the Hajj. One of Islam’s five pillars is performing the hajj, or the holy pilgrimage to Mecca in Saudi Arabia. Eid is celebrated right after Muslim pilgrims cross Mount Arafat.

El-maulud is the commemoration of the Prophet Mohammed’s (peace and blessings of Allah be upon him) Mawlid birthday.

Music

The Hausas play a variety of musical genres. Their folk music contributed components like the goje, a one-stringed violin, to the creation of Nigerian music, which has been influential. Traditional Hausa music can be divided into two main categories: urban court music and rural folk music.

Musicians selected primarily for political rather than musical reasons perform ceremonial music, or rokon fada, as a prestige symbol. At the weekly sara, the emir’s declaration of authority held every Thursday night, ceremonial music is played.

Courtly praise singers, such as the well-known Narambad, are committed to extolling the merits of a benefactor, such as an emir or sultan. Kettledrums, kalangu talking drums, and the kakaki, a type of long trumpet adapted from the Songhai cavalry, are used to accompany praise songs.

The music of the Bori religion, also famed for its melody, and the asauwara dance performed by young girls are examples of rural folk music. Trans-Saharan trade has carried it as far north as Tripoli, Libya. The trance music of the bààríí cult is performed on a calabash, lute, or fiddle.

Women and other disadvantaged groups have trances during ceremonies, during which they act strangely—for example, imitating pigs or engaging in sexual activity. It is claimed that these individuals are controlled by a character, each with a unique litany, or kírààrì. The Niger Delta is home to such trance cults, also known as “mermaid cults.”

Popular Hausa musicians include Ibrahim Na Habu, who plays the little violin known as a kukkuma, Dan Maraya, who plays the one-stringed lute known as a kontigi, and Hamman Shata, who sings while backed by drummers.

Food

The majority of the food that the Hausa people cook is flour made from grains like sorghum, millet, rice, or maize, which may be used in many different recipes. Tuwo, as it is commonly called in Hausa, is this dish.

Typically, breakfast comprises of cakes called funkaso (fried cakes served with sugar) or kosai (fried cakes made from crushed beans soaked for a day). Kunu or koko, a type of porridge with sugar, can be eaten with any of these pastries.

Tuwo da miya, a hearty porridge with soup and stew, is typically served for lunch or dinner. Tomatoes, onions, and regional spices are typically used to produce the soup and stew.

When making the soup, other ingredients like spinach, pumpkin, or okra are added along with spices. Because of Islamic dietary rules, animal—goat or cow meat, for example—must be used to cook the stew instead of pork. The Hausa people also eat beans, peanuts, and milk as a supplemental protein source.

The most well-known Hausa dish is probably suya, which is a spicy skewered beef dish similar to a shish kebab that is relished as a delicacy throughout most of West Africa and in some parts of Nigeria. Another popular dish is balangu, sometimes known as gasshi.

Kilishi is the name for Suya in a dried form.

Literature

Since writer Balaraba Ramat Yakubu gained prominence in the late 1980s, a contemporary literary movement led by female Hausa writers has expanded. With time, the authors gave rise to a distinct subgenre known as Kano market literature, so called because the books are frequently self-published and offered for sale in Nigerian markets.

The misogyny and fanaticism of Islam have made it difficult for women to work and write freely. But these books are popular, especially with female readers, because of their subversive nature. They are typically romantic and family dramas that are otherwise difficult to find in the Hausa language. Another name for the genre is “love literature,” or littattafan soyayya.

Traditional sport of the Hausa people

The Hausa people have a rich legacy of traditional sports, like boxing (Dambe), stick fights (Takkai), wrestling (Kokawa), and others. These sports were first held to commemorate harvests, but they have evolved into entertainment events throughout the years.

Dambe

The Hausa people of West Africa practice a harsh traditional combat art known as dambe. Its genesis remains a mystery. Edward Powe, an expert in Nigerian martial arts, has noticed that Hausa fighters’ stance and single-wrapped fist bear strong resemblances to pictures of ancient Egyptian boxers from the 12th and 13th dynasties.

It began among the lower classes of the Hausa Butcher caste divisions, then evolved into a means of military training, and then through centuries of Northern Nigerians, became a sporting event. There are no time limits and the fight is done in rounds of three or less. If a fighter is knocked out, stops moving, has their knee, body, or hand touch the ground, or is stopped by an official, the round is over.

Dambe’s main weapon is the “spear,” which is one dominant hand that is wrapped in thick cotton bandages from the fist to the forearm. The cord is knotted and dipped in salt, and it is left to dry for maximum body damage to opponents. The other arm, kept open, is used as a “shield” to protect the fighter’s head from blows from opponents or to grab an opponent. Fighters typically suffer from broken noses, split brows, and even brain damage.Although the warriors in dambe may win cash, livestock, agricultural products, or jewelry, the main reason they fight is to become famous among communities and clans that represent them.